Inspiring the next generation of ecologists – by Nick Powell

In their early years, children are closer to the natural world than at any other point in their lives. They burrow in deep grass and meld their bodies into the Earth’s caress beneath them, before settling to gaze skyward at sailing clouds. They finger-twirl blades of grass and twiddle them in their mouths, until the sweetness is sucked dry.

They love the smell and feel of soil. Mud is heaven sent. They coil with worms around their hands and wonder at ladybirds as they tickle up their arms.

Nobody tells them to do it. It all comes naturally and their imaginations flit in delight, allowing them to become waltzing bees, dive-bombing dragonflies and spiders skimming across a web.

But for many children that link to nature soon begins to ebb away and the modern child often ceases to be in touch with wildlife. They have stopped being wild.

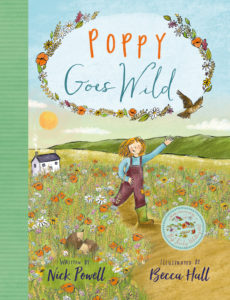

My mission was simple when I decided to write Poppy Goes Wild, a book for children about a young girl rewilding her grandad’s farm. I wanted to encourage children to look after wildlife. Once you become a true convert to that role, I am convinced that you will do it for the rest of your life.

Poppy needed to be appealing to children, so making her fun, with a bright intelligence and heaps of determination was essential. Poppy, and therefore the young reader, had lots to learn if she was going to stand any chance of restoring the farm to a time when wildflowers swooned, and kingfishers swirled alongside surfing otters.

Poppy’s grandad had lost touch with the riotous abundance of wildlife he loved to be among when he was a boy. His intensive farming practises, use of pesticides, and industrial pollution had led to rapid declines in all but the hardiest of mammals around the farm.

The book is purposefully not overtly critical of Poppy’s grandad’s actions as a farmer. It acknowledges that along with most farmers, he followed the technological developments of the time to increase his yields. However, like so many of us, he failed to sufficiently notice that the post-war advances were wreaking destruction by stealth all around us.

The book is purposefully not overtly critical of Poppy’s grandad’s actions as a farmer. It acknowledges that along with most farmers, he followed the technological developments of the time to increase his yields. However, like so many of us, he failed to sufficiently notice that the post-war advances were wreaking destruction by stealth all around us.

Aged 14, I was transfixed by the magical sight of an otter catching fish and sunning itself at the river’s edge. The moment became a sparkling jewel in my memory bank, but it was decades before I saw another otter in the wild, and that only happened as the result of a river conservation project. Otters had almost become extinct in England and I hadn’t even noticed.

Poppy is relentless in her quest and her grandad cheerfully keeps up, reconnecting with how he and his father used to manage the land. Grandad immediately stops using pesticides and large areas of land are left to grow wild. Newly planted flower meadows lure back the bees and butterflies, and over time hares start to breed again in the overgrown grassy areas.

Poppy co-opts her classmates to clean up the river and it is restored to its natural flood plain, eventually leading to the triumphant return of the otters, who hadn’t been around since her grandad was a boy.

The story draws on inspirational rewilding schemes like those at the Knepp Estate in West Sussex and the Trees For Life project in Scotland, and on the transformations being carried out by farmers around the country. But it also taps into smaller projects where schoolchildren are planting trees and wildflowers, and clearing up rivers. The Earth Restoration Service is a pioneering organisation working in this field.

There is a growing body of research showing the benefits of children getting closer to nature, which has particularly been in evidence during the pandemic. The world of education, not least as a result of the pressure of striking schoolchildren, has really begun to embrace the idea that the more children learn about nature and sustainability, the better prepared they will be to face the challenges of our constantly changing world.

My hope is that Poppy will help to scatter seeds in homes and classrooms to help in that process. The CIEEM website invites you to click if you want to be an ecologist or environmental manager. I would love to see every child in the classroom putting their hand up to that question, regardless of the career path they eventually take.

It is highly encouraging to see that improved management of the planet is now an urgent priority for young people. Crucially, that sense of urgency is becoming multi-generational and the vast majority of western politicians see it as an essential vote winner.

Biden’s Green New Deal will hopefully usher in a real era of change and the UK Government is making tiny steps in the right direction. But we need to see words translated into action and that means a supercharging of investment across the whole spectrum of management of the environment and energy supply.

Private enterprise has inevitably seen a huge opportunity and there is an exciting new generation of innovators trying to create solutions to the environmental challenges around us. Some are forging ahead with game-changing companies in areas like microbial discovery of new natural predators, heralding the arrival of non-harmful bio-fertilisers, others are doing DNA-based monitoring to help to combat the reduction of biodiversity.

But with biodiversity numbers in the UK still in decline, we know that a great deal of work remains to be done and vigilance is more urgent than ever. The work of CIEEM members has never been more vital.

I hope that some of the Institute’s future members will have grown up reading Poppy Goes Wild, and that they may have been motivated by seeing one small way in which damage to biodiversity can start to be reversed. One of the greatest things about our planet is that we learn new things about it every day. The earlier in life that you learn how to protect it, hopefully the better you will be as a guardian of its future.

Nick is a multi-award winning television producer whose credits include launching the series Supernanny, Escape to River Cottage, Nigella Bites, Food Unwrapped and Blood, Sweat and T-Shirts. Born and raised in the Black Country, Nick grew up with a strong appreciation of the rivers, wild meadows and rolling hills of the surrounding countryside. As a teenager he was transfixed by the magical sight of an otter catching a fish and sunning itself on the riverbank. He didn’t see another one in the wild until decades later, when rivers began to be cleaned up. He is now lucky enough to divide his time between living alongside the South Downs National Park and the wildflower meadows of the French Alps.

Nick is a multi-award winning television producer whose credits include launching the series Supernanny, Escape to River Cottage, Nigella Bites, Food Unwrapped and Blood, Sweat and T-Shirts. Born and raised in the Black Country, Nick grew up with a strong appreciation of the rivers, wild meadows and rolling hills of the surrounding countryside. As a teenager he was transfixed by the magical sight of an otter catching a fish and sunning itself on the riverbank. He didn’t see another one in the wild until decades later, when rivers began to be cleaned up. He is now lucky enough to divide his time between living alongside the South Downs National Park and the wildflower meadows of the French Alps.

Blog posts on the CIEEM website are the views and opinions of the author(s) credited. They do not necessarily represent the views or position of CIEEM. The CIEEM blog is intended to be a space in which we publish thought-provoking and discussion-stimulating articles. If you’d like to write a blog sharing your own experiences or views, we’d love to hear from you at JasonReeves@cieem.net.