Green Matters at Hay-on-Wye Festival – by Mandy Marsh

In T.H. White’s The Sword in the Stone, the future King Arthur, known as Wart, is tutored by Merlyn the wizard. Merlyn is aware of Wart’s destiny because he is, according to White, “living backwards through time”. Over the years growing up in the Forest Sauvage, Merlyn magically turns Wart into a variety of animals so he can experience their different societies, expectations, fears and joys.

I was reminded of this recently when I attended the launch of a new Climate Fiction Prize[1] at Hay-on-Wye Literary Festival. Hay (Y Gelli in Welsh) is a small market town mostly in Wales, though if you walk down Newport Street towards the Coop you’ll suddenly find yourself in England. The resident population numbers around 2,000 but every year the town welcomes approximately 80,000 visitors to the Festival, for which it is world-famous.

Hay goes green

Although it began as a literary festival, Hay has become increasingly concerned with environmental matters. It recently severed its contract with sponsor Baillie Gifford because of its links to fossil fuels[2], and it’s particularly poignant that it sits on the beautiful river Wye, which is now a byword for agricultural pollution[3].

The festival site is a perfect size; everything is in one location, which is just big enough to keep you interested but not so big that you get lost and exhausted. There are taps to refill your water bottle and washing stations for your re-usable cups. Food was served on cardboard dishes with bamboo utensils, so everything went straight into a bin for later composting. The official campsite is operated by Tangerine Fields, a company providing pre-pitched tents which it takes from festival to festival (and recycles at end of life), to combat the terrible waste of abandoned tents seen at the likes of Glastonbury.

I was at Hay at the invitation of Aberystwyth University, and I took the opportunity to attend several other environmental events (reminder for next year: book early, as many had sold out). It had rained earlier in the week but the sun was out for my visit, so I literally made Hay while the sun shone.

Difficult conservation choices

The Aberystwyth University event[4] centred on the role of wildlife in alleviating poverty and identifying conservation priorities. How do we balance the desire to protect threatened species with the needs of human populations? Who decides? For any conservation project to be a success, it is vital to involve the local communities. As a little behavioural experiment, the audience was asked to turn to a stranger and begin a conversation. Even in a non-threatening arena of like-minded people, some found this more difficult than others. How much harder, then, to approach communities in Africa and suggest they stop killing rhinos. In a memorable response, conservationists were told “Rhinos are white men’s toys”. Distasteful though it might be to some, hunting has contributed greatly to the conservation of some animals; what if the only way to save the rhinos is to legalise the trade in rhino horn?

People engagement

The importance of community was a strong emerging theme throughout the Festival. Despite the connection with a world-famous literary festival and the world’s largest secondhand and antiquarian book centre, Hay’s public library was due for closure until it was rescued by community effort. It is now a community hub which is developing networks to, amongst other things, prepare citizens for the challenges of climate change. This includes – at their own request – setting up a Climate Change Club for young people.

In Mobilising for the Future[5], the panellists recognised the paralysis and underwhelm afflicting so many people, especially young people, when it comes to facing these challenges. Jack Harries is not one of these; as co-founder of Earthrise and a social media influencer, he is seeking to engage with new, younger audiences. Jane Davidson, the former Welsh Government Minister who instigated Wales’s ground-breaking Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015 (the first piece of legislation in history to place regenerative and sustainable practice at the heart of government), wants to rewrite the rules for good decision-making. Her motto is Never argue, only help, and she is keen to hear of your frustrations of working within the system. Meanwhile, Julian Rhind-Tutt – who described the average age of the audience as ‘wise’ – would like to see a mini United Nations amongst schools, where students from around the world can talk about problems and solutions.

The failure to secure community buy-in was most spectacularly seen in Wales with the Summit to Sea project. While its aims were laudable – joined-up thinking about rewilding nature and landscapes from mountain top to coast – the project failed to talk to farmers in the early stages and the resulting backlash badly damaged relations between the agriculture and ecology sectors. Part of the problem was that NGOs can raise funds for specific projects with clear outcomes, but struggle to find funds to cover the vital initial discussion and stakeholder engagement stage. Who is going to fund you if you can’t say what the end point is going to be?

Global challenges

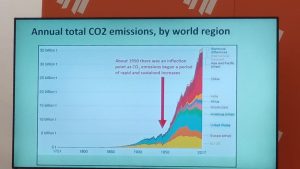

Dharshini David, Chief Economics Correspondent of BBC News, says that economics is not about money, it’s about choices. She was at Hay to discuss her new book Environomics [6], which asks what is happening globally, who is driving it and, crucially, what will this mean for us. Until the ‘polluter pays’ principle is adopted as standard, companies will continue to throw returned items of online purchases straight into landfill because it’s cheaper than unpacking them, and it will still be cheaper to transport items halfway round the world than to produce them locally.

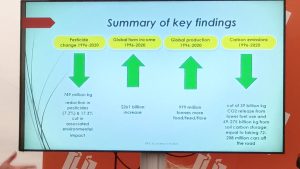

Global food production was the subject of a Food for Thought discussion[7]. There will be an estimated 9 billion people to feed by 2050; rice, wheat and maize are the three main world crops which provide 67% of human food calories, and they are all vulnerable to the effects of climate change. The panel of agricultural experts advocate a three-pronged approach:

- High-intensity agriculture using technology to maximise yields and mitigate negative environmental impacts. This includes gene-editing[8] (which fast-tracks natural mutations) to produce plants which are, for example, drought tolerant, disease resistant, or with lower sugar or gluten content. This could enable even some of the poorest farmers to increase their harvests.

- Lower intensity agriculture, which can sometimes provide better habitat for certain species than undisturbed natural habitats (land sharing)

- Reversion of some agricultural land back to natural habitat (land sparing)

The power of nature fiction

When you’re dealing with such difficult, highly technical and practical decisions in the ‘real’ world, it might seem that launching a prize for the best climate fiction novel is lightweight in comparison. However, nature fiction can have profound effects on readers, especially at a young age, and it’s right that it should be recognised. At the launch, panellists discussed the influential role of climate fiction. Writer Amitav Ghosh has commented:

“… fiction that deals with climate change is almost by definition not of the kind that is taken seriously … [it] is often enough to relegate a novel or short story to the genre of science fiction … [as though] climate change were somehow akin to extraterrestrials of interplanetary travel.”[9]

There is something ironic about this, given that climate change predictions rely on collecting solid, scientific data. One welcome new approach for writers might be to move away from distressing dystopia fiction and instead write about the possible: what might the future look like if we were able to implement climate solutions and bring about a just transition? Maybe this is what our young people need to draw them from their apathy and disassociation: imaginative writers who can show that another way is possible.

Another approach would be to lose the human-centric view of the world, perhaps by focusing on animals. Watership Down by Richard Adams probably influenced a whole generation of conservationists. As well as basing the book on a real place, Adams relied heavily on The Private Life of the Rabbit written by his friend Ronald Lockley, the Welsh ornithologist and naturalist.

Which brings us back to The Sword in the Stone[10], a book I read as a teenager and probably haven’t directly thought about much since, but I see now that it had a more profound effect on me than I realised. Through Wart’s eyes I learned of the horrors of the authoritarian ant nest, the beauty of the wild geese who recognise no human land boundaries, and the dangers of predatory pike in the castle moat. How telling that Merlyn (or rather, T.H. White) thought that the most fitting education for a future king was not how to wield a sword or command an army, but instead to immerse him in the natural world. If only our politicians could have a similar education, how different our society might be. It’s up to us, then, to engage our children with their environment as much as possible, and overhaul the National Curriculum. I’m as keen on the proper use of grammar as the next nerd, but we have surely lost the plot when we are stressing the importance of fronted adverbials to primary school children [11] when what they really need is more nature.

Many thanks to Aberystwyth University for my complimentary ticket and for introducing me to a new experience.

Mandy Marsh is Wales Project Officer with CIEEM. She has just started re-reading The Sword in the Stone after a gap of decades, and is finding it even better than she remembers.

[1] Climate Fiction Prize Launch, Hay Festival 2024. Writers Nicola Chester, Madeleine Bunting, Lucy Stone, with Andy Fryers, Hay Festival Global Sustainability Director.

[2] Hay Festival suspends Baillie Gifford sponsorship https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/ce99lg5r247o

[3] https://friendsoftheriverwye.org.uk/ Accessed 20/06/2024

[4] Penguins, Rhinos and Poverty. Hay Festival 2024. Professor Darrell Abernethy, Head of School of Veterinary Sciences and Jennifer Wolowic, Principal Lead of Dialogue Centre from Aberystwyth University, with Oliver Smith from WWF.

[5] Mobilising for the Future, Hay Festival 2024. Jane Davidson, Julian Rhind-Tutt and Jack Harries, with Nicola Cutcher.

[6] David, D. (2024) Environomics – How the Green Economy is Transforming Your World. Elliott & Thompson Limited

[7] Food for Thought, Hay Festival 2024. Jonathan Harrington (Cardiff University), Prof. Tina Barsby (University of Cambridge), Prof. Denis Murphy (University of South Wales) and Agricultural Economist Graham Brookes.

[8] https://www.integra-biosciences.com/united-kingdom/en/blog/article/what-crispr-cas9-and-how-does-it-work

[9] Ghosh, Amitav (2016) The Great Derangement. University of Chicago Press.

[10] White, T.H. The Sword in the Stone. Collins. First published in 1938, it later became the first part of the quartet The Once and Future King.

[11]Battle on the adverbials front: grammar advisers raise worries about Sats tests and teaching (2017) https://www.theguardian.com/education/2017/may/09/fronted-adverbials-sats-grammar-test-primary Accessed 13/06/2024