Monitoring – essential for good practice in ecological restoration

By David Parker & Oliver Barnett

CIEEM’s Ecological Restoration Special Interest Group has been working to produce ecological restoration guidance, a programme summarised in an earlier blog Rebuilding Nature. The first guidance set out ten principles for ecological restoration projects which has lead on to the publication of five Overarching Topics which provide best practice guidance for the design, implementation and monitoring of these projects.

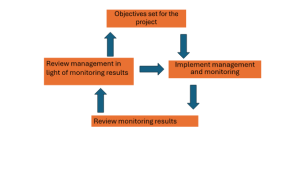

Why is monitoring so important? It is because any ecological restoration project should set clear, measurable goals, and monitoring is the mechanism through which it can be seen whether the project goals are being achieved and, if not, why not. Remedial action can be taken to set the project back on track, or the project can be altered through the principles of adaptive management. However, none of this will be effective without good evidence, obtained through a bespoke monitoring programme, which can be over a long period. This process can be summarised by a simple flowchart:

The monitoring guidance sets out this thinking in more detail and explains out how to design a monitoring plan and how to use the results. Embedding monitoring into project planning is essential and this should include an adequate budget for carrying this out. Fortunately, there are an increasing number of monitoring techniques which can be used. The guidance sets these out, recognising that new technology is becoming increasing useful, such as drones, acoustic monitoring and eDNA.

In the past there have been many ecological restoration projects which have not had effective monitoring as part of their short, medium and long-term management. How can a project manager be sure of their actions without accurate information on whether the project’s objectives are being met? This is not just a matter of outcomes for nature and people; it is also about cost and value for money. Project funders increasingly want value for their investment and practitioners will need good evidence to demonstrate this. Monitoring will provide it!

We will seek to update and improve the guidance, and your feedback will help in achieving this – we look forward to any feedback. Please contact the Working Group via the Ecological Restoration SIG on er@CIEEM.net.

Mire restoration and reintroduction site for White-faced Darter Leucorrhinia dubia. An example of an ecological restoration project with both habitat and species objectives, managed by Cheshire Wildlife Trust. Dolittle Moss, Delamere Forest, Cheshire, 31 July 2020. © David Parker.

In 1999/2000, sheep were removed from Cwm Idwal NNR following decades of high sheep numbers. The objective was the restoration of upland and arctic-alpine vegetation which had been supressed by grazing. A monitoring programme was set up, from the outset, by the Countryside Council for Wales using a set of permanent recording quadrats; this monitoring continues to the present day, now by Natural Resources Wales. The two photographs show the recovery of ericaceous vegetation, between 22 July 2008 (upper) and 21 August 2025 (lower). Cwm Idwal, Eryri, North Wales © David Parker.