HS2’s Bat Mitigation Structure: Why it exists and what it means

By David Prŷs-Jones MCIEEM

Few aspects of HS2 have generated as much commentary within the media and environmental sector recently as the bat mitigation structure which will run alongside Sheephouse Wood in Buckinghamshire. To some, it has become a lightning rod for wider debates about planning, cost, and environmental legislation.

As a member of the Chartered Institute of Ecology and Environmental Management (CIEEM) for over 15 years, I share the profession’s commitment to improving public understanding of environmental legislation and robust ecological practice. But I do not accept the claim that building this structure was a “blunder” that could easily have been avoided. The reality—rooted in ecology, existing legislation, design constraints, and long‑term rail operations—is more nuanced and deserves an explanation.

This blog attempts to set out why the bat structure exists, what it is and attempts to provide context and clarity on cost and its design.

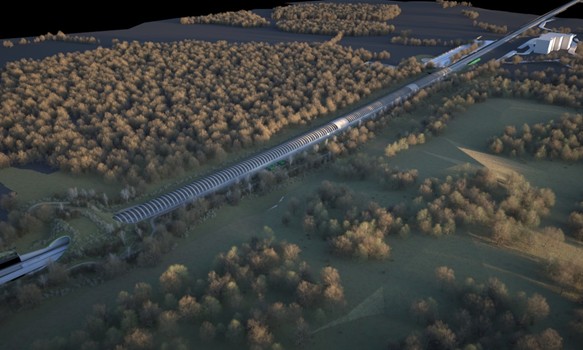

Visualisation showing the south portal of the bat mitigation structure (Credit: HS2 Ltd)

Why the structure exists?

Sheephouse Wood is part of a wider landscape including Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI), ancient woodlands, pastures and hedgerows known as Bernwood Forest which is situated between Bicester and Aylesbury. The presence of Bechstein’s bat (Myotis bechsteinii) – an extremely rare and protected woodland specialist – within the Bernwood landscape was identified at an early design stage of the project through extensive surveys carried out by ecologists working on HS2.

UK law requires avoiding harm to bats and the provision of mitigation where impacts occur. HS2’s 2013 Environmental Statement, part of the High Speed Rail (London-West Midlands) Bill, highlighted the need for providing robust protection and crossing measures for bats in this sensitive landscape. Natural England have confirmed HS2 identified this requirement over a decade ago. This is not a last-minute fix—it was embedded early in the design process.

What does it look like?

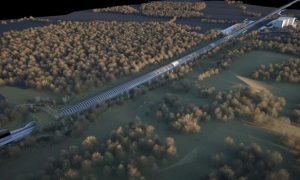

The bat mitigation structure is a 900m-long, 10m-high porous corridor of over 500 precast concrete arches with mesh panels, integrated with a green bridge and underpass. Once complete it will work to shield adjacent bat populations from passing high speed trains, spanning four tracks’ width, allowing not just for HS2’s high‑speed lines but also for passive provision for freight and local services on the adjacent conventional corridor—including future capacity for direct trains from Aylesbury to Milton Keynes via East West Rail (EWR). The HS2 alignment follows an existing railway corridor which was used by freight trains until recently, reducing habitat fragmentation compared to creating a new route through this sensitive landscape. Its 120-year design life will ensure lasting durability for an expanding rail network.

Visualisation showing the bat mitigation structure, including the associated green bridge (Credit: HS2 Ltd)

Why not move the railway?

Could rerouting avoid the need for the bat structure? Not realistically. The corridor is hemmed in by Sheephouse Wood SSSI, industrial assets, and local communities (including the village of Calvert). The rail route here follows the existing line, and interfaces with critical EWR infrastructure. In this context, “moving the railway” would simply trade one set of impacts for another, including greater ecological loss or community impact, rather than eliminate the legal obligation to protect bats.

How much will it cost?

The structure costs approximately £95 million (2019 prices), with EWR contributing roughly a third of the cost. Headlines often ignore that inadequate mitigation risks legal challenge, delays, and further expense. The real question is value: delivering ecological function, legal compliance, operational safety, and future connectivity in one solution.

Because the structure is high‑profile and of high-value, the options available to build it were rightly interrogated hard. A 2021 review by DfT, DEFRA, and Natural England found no better solution that met species protection law and reduced cost. Independent design review by Arup confirmed the precast arch/mesh approach as the best balance of compliance, cost, and risk. If a better solution existed, which was materially cheaper, simpler, and still legally robust solution, these reviews would have surfaced it.

What happens next?

Construction is only the start. HS2’s ecology teams have been monitoring the bat populations within the wider area for over a decade and will continue post‑construction monitoring of bat activity, behaviours, and crossing success. We will also continue to publish information on the bat structure online and share the outputs of our monitoring work with Natural England (as part of the bat licence the project has) and other conservation groups – so practitioners can see outputs, and we can improve the way we work.

Progress on construction of the bat mitigation structure with Sheephouse Wood behind – November 2025 (Credit: HS2 Ltd)

The bigger picture

This is a case study in how modern infrastructure interfaces with rare species and protected landscapes. It has forced difficult trade‑offs—between design efficiency, legal compliance, and ecological function. It has also become entangled in wider political narratives about planning reform and environmental regulation, sometimes obscuring the facts. Balanced commentary from multiple conservation bodies has reminded us that development and nature must go hand‑in‑hand, and that well‑designed green infrastructure can benefit bats and other wildlife when implemented appropriately.

As environmental professionals, we all have a responsibility to explain our work clearly, to engage with legitimate concerns, and to call out inaccuracies. Rather than judging on hyperbolic headlines, we should consider evidence, legislation, and site realities. The bat structure is not a “blunder”—it is a professional response to a complex problem at the interface of nature and national infrastructure.

About the author

David Prŷs-Jones MCIEEM is Head of Natural Environment at HS2 Ltd. He leads a variety of topic teams, including ecology and landscape, and is committed to delivering meaningful outcomes for both nature and local communities along the line of the project. He would welcome any conversations about improving environmental outcomes. David can be contacted via LinkedIn here.