Rethinking River Catchments: Why Small Waters Hold the Key to Biodiversity and Climate Resilience

In the realm of freshwater conservation, mainstream views have long favoured the restoration of large habitats, rivers, lakes, and expansive wetlands. These systems dominate the landscape, form extensive networks, and seem intuitively more capable of supporting diverse species and natural processes. Yet, a growing body of evidence suggests this approach may be the wrong way around.

Tiny is mighty

A growing body of evidence shows that it’s the small places that support most biodiversity – the headwater streams, ponds, small lakes and diversity of small wetlands (springs, flushes etc.). Individually they are small, but they are highly numerous and heterogeneous, and taken together are where most freshwater biodiversity, in particular threatened freshwater biodiversity, lives in catchments. Freshwater creatures can move between these small habitats as well as larger ones like rivers, even if not physically connected.

Take ponds, which make up most of the standing water in a catchment. Their small catchments can make them free of agricultural runoff and other pollution, meaning they often provide the only resource of clean water in a landscape. There is a significant overlap in the biodiversity of ponds and other freshwaters, including rivers, but many more species are dependent on ponds, especially threatened species.

Headwater catchments are vital for catchment biodiversity and hydrology. These upper catchments act as ecological control towers, regulating water flow, filtering pollutants, and buffering downstream systems against hydrological shocks. When degraded, they accelerate runoff, erode soils, and destabilize entire river networks.

‘Small’ is relative – this creature, the threatened Orange-horned Green Colonel (Odontomyia angulata) lives in small, warm pools in fens fed by calcium-rich springs.

‘Small’ is relative – this creature, the threatened Orange-horned Green Colonel (Odontomyia angulata) lives in small, warm pools in fens fed by calcium-rich springs.

Pressures

Freshwaters and their biodiversity are under more threat than any other group of organisms. Given the many demands our societies make on water and how we manage water and land for economic gain, this should hardly be surprising.

Pollution from sewage, especially of large rivers and lakes, has risen up the national consciousness as a major environmental issue. However, more important for the rich freshwater biodiversity that remains in the UK are the neglect and lack of resources for the good management of thousands of ponds, wetlands and headwaters, together with the more insidious pressure of diffuse nutrient pollution from e.g. agriculture.

Added to this is the instability of climate change, disrupting rainfall patterns, increasing droughts and flash floods. These will further stress freshwater ecosystems, both directly and by our increasing demands for ever scarcer water resources.

Building Resilience from the Top Down

In our degraded landscapes, small freshwaters offer practicable solutions to reversing the decline in freshwater biodiversity. For example, small streams where small wastewater discharges make up a significant proportion of flows are easier to address e.g. through simple improvements or closures, than major upgrades to large sewage works. Ponds can be created in clean catchments. The importance of small wetlands can be recognised, and their management and restoration prioritised. These actions are more cost effective than large interventions, which often have negligible outcomes or are simply intractable. They can also be multiplied across sub-catchments, local communities and landowners. Not that we shouldn’t be aspiring to fix individual big problems, but current policy and regulations focus solely on these.

A Free Water Surface Constructed Wetland

Strategically, this means shifting investment upstream. Rather than reacting to flooding and pollution downstream, we can prevent it by restoring headwaters and their wetlands, putting resources into managing the biodiversity riches of these places, and embedding nature-based solutions into land management.

Though individually upstream, headwater catchments collectively shape the resilience of entire river systems. A degraded few can destabilise the whole; at scale, taken together they amplify resilience. This top-down approach aligns with climate adaptation goals, and has potential for a whole range of societal benefits, including reduced long-term costs, healthy soils and water, and community wellbeing.

Collaborating and Monitoring

This shift in perspective is gaining ground in UK freshwater conservation. Earlier this year, a group of NGOs published the Charter for Small Waters, which urges the government to consider small freshwaters as part of its promise to ‘fundamentally transform’ the water system and improve outcomes for people and the environment.

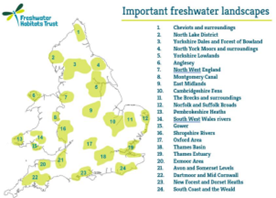

Important Freshwater Landscapes in England and Wales

Important Freshwater Landscapes in England and Wales

Delivering lasting outcomes for biodiversity and development requires joined up thinking. Farmers, planners, conservationists, and communities must codesign solutions that balance ecological integrity with economic needs. Catchment partnerships and nature-based solutions hubs facilitate this collaboration, aligning land management with wetland protection.

Importantly, monitoring efforts, including the regulations that mandate monitoring, must evolve to include small waters, capturing their contributions to catchment health and biodiversity.

Summary

Small freshwater habitats – ponds, headwater streams, and small wetlands – are the unsung heroes of river catchments. Though individually small, they collectively support most freshwater biodiversity and offer scalable, cost effective solutions to ecological restoration and (potentially) climate resilience. By shifting focus from large water bodies to these foundational systems, and fostering cross-sector collaboration, we can restore degraded landscapes, protect threatened species, and build a more resilient future from the top of the catchment, downstream.

About the Authors

David Morris MCIEEM is a senior plant ecologist at Freshwater Habitats Trust, the UK’s leading charity working to conserve all freshwater habitats and their biodiversity. His special interest is fens, especially smaller spring-fed mires found in headwaters. David is also the Botanical Society for Britain and Ireland’s (BSBI) county recorder for Oxfordshire and a member of the CIEEM Freshwater Special Interest Group.

David Morris MCIEEM is a senior plant ecologist at Freshwater Habitats Trust, the UK’s leading charity working to conserve all freshwater habitats and their biodiversity. His special interest is fens, especially smaller spring-fed mires found in headwaters. David is also the Botanical Society for Britain and Ireland’s (BSBI) county recorder for Oxfordshire and a member of the CIEEM Freshwater Special Interest Group.

Helena Du-Roe BSc (Hons), MSc, MCIWEM, C.WEM is a chartered Principal Hydrologist at Enzygo Ltd, a multidisciplinary environmental consultancy. She leads on flood risk modelling and hydrological assessments, supporting sustainable development and climate resilience across the UK. Helena is a member of the CIWEM Early Careers Steering Group, where she advocates for professional growth, mentors emerging talent, and contributes to shaping inclusive pathways for future water and environmental professionals.

Helena Du-Roe BSc (Hons), MSc, MCIWEM, C.WEM is a chartered Principal Hydrologist at Enzygo Ltd, a multidisciplinary environmental consultancy. She leads on flood risk modelling and hydrological assessments, supporting sustainable development and climate resilience across the UK. Helena is a member of the CIWEM Early Careers Steering Group, where she advocates for professional growth, mentors emerging talent, and contributes to shaping inclusive pathways for future water and environmental professionals.