Mangroves, Meadows, and Reefs: Nature’s Frontline Defenders Against the Climate and Biodiversity Crisis

Mangroves, seagrass meadows, and coral reefs are nature’s frontline defenders in the fight against climate change and biodiversity loss. These blue carbon sinks not only shield coastlines and support biodiversity but also sustain local economies and hold immense cultural value. Protecting and restoring these ecosystems is critical, and understanding their roles, threats, and success stories is essential for global conservation efforts.

Mangroves

Covering less than 1% of the planet, mangroves, intertidal forested swamps, form one of the most biodiverse habitats on Earth. Mangrove trees uniquely survive in saline water through specialised root filtration systems, which allow them to thrive where most other trees cannot.

Key benefits of mangroves

Mangroves provide numerous ecological and social benefits. Their dense root networks absorb wave energy, substantially reducing flood risks, and mangrove belts as narrow as 80m can cut wave heights by 80%, offering vital protection to coastal communities. These ecosystems are also exceptional carbon sinks, storing three to four times more carbon in their soils than terrestrial tropical forests. Beyond these direct benefits, mangroves protect coral reefs by trapping sediment, regulating nutrients, and providing shade. They also support fisheries, timber, and other community resources.

Threats to mangroves

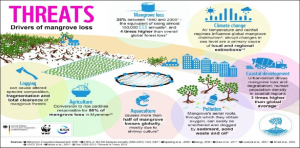

Despite their value, mangroves face significant threats from human activity and environmental change, as outlined in the diagram below. Nearly 50% of mangrove-associated mammals face extinction, and between 20 and 35% of the world’s mangroves have disappeared since 1980.

Stories of mangrove restoration

The Global Mangrove Alliance has set an ambitious target to increase mangrove coverage by 20% by 2030, aiming to restore 600,000 hectares by 2024. Funding gaps, challenges with community engagement, and the long timelines needed for regeneration remain challenging, but important lessons are being learned.

Encouragingly, community-driven projects in El Salvador, have restored over 70 hectares by reopening tidal channels, while India’s Tamil Nadu Forest Department engages local councils in replanting initiatives. In Kenya, the Mikoko Pamoja Project combines mangrove restoration with carbon credit initiatives that directly benefit local livelihoods. Technology, for example the Global Mangrove Watch platform, provides real-time monitoring, helping governments and conservation organisations prioritise action.

Together, these efforts highlight both the challenges and opportunities of large-scale mangrove restoration and underscore the importance of protecting mangroves.

Seagrass Meadows

Seagrass meadows are underwater flowering plants that form dense, lush beds in shallow coastal waters, serving as vital ecosystems for numerous marine species. These meadows provide critical habitat for a range of species, including sea cows, sea turtles, and various fish.

Key benefits of seagrass meadows

A well known feature of seagrass meadows in carbon sequestration, with these habitats, storing up to 18% of the world’s oceanic carbon. However, the benefits from seagrass meadows are broad and cross-sectoral, as illustrated clearly in the diagram below.

Threats to seagrass meadows

Seagrass meadows face multiple threats from human and environmental pressures. Runoff from agriculture and industry lead to water quality degradation and algal blooms that can smother seagrass beds. Coastal development, including dredging and construction, disrupts seagrass habitats and can lead to direct loss of meadows. Climate change exacerbates these issues by increasing sea temperatures and causing ocean acidification, both of which negatively impact seagrass health. Despite their ecological importance, seagrass meadows have been in decline for nearly a century due to various anthropogenic and environmental pressures. Current estimates suggest that approximately 7% of seagrass meadows are lost each year, underscoring the urgency of restoration and protection efforts.

Stories of seagrass meadow restoration

In the UK, we are setting an example of effective seagrass restoration. The Solent Seagrass Restoration Project, led by local scientists and the Hampshire and Isle of Wight Wildlife Trust, maps, monitors, and restores seagrass meadows in southern England. Complementing this, Swansea University’s Seagrass Ocean Rescue develops transplanting and seed-based techniques while tackling social, biological, and governance challenges. These coordinated local efforts show how research and community engagement can revive seagrass habitats.

Coral Reefs

Coral reefs are diverse underwater ecosystems held together by calcium carbonate structures secreted by corals which are found in the photic zone of the sea. These reefs are often referred to as the “rainforests of the sea” due to their rich biodiversity. Despite covering less than 1% of the ocean floor, coral reefs support approximately 25% of all marine species.

Key benefits of coral reefs

Coral reefs protect coastlines from erosion, support fisheries, boost tourism, and provide livelihoods for millions while sustaining diverse marine life. Additionally, coral reefs are vital for scientific research, offering insights into marine biology, ecology, and climate change through the diverse range of flora and fauna that inhabit these reefs.

Threats to coral reefs

Coral reefs are under immense pressure from a range of human-induced and environmental threats. Climate change drives ocean warming and acidification, causing widespread coral bleaching and leaving reefs weakened and vulnerable. Overfishing disrupts the delicate ecological balance, removing key species that help maintain reef health. Pollution, from agricultural runoff to plastic waste, degrades water quality and introduces toxins that harm corals. Coastal development such as dredging and land reclamation increases sedimentation that smothers corals and reduces their ability to grow. Together, these stressors are eroding the resilience of coral reefs, putting both biodiversity and reliant human communities at risk.

Stories of coral restoration

Despite the threats, coral reef restoration is showing promising results. Techniques such as coral gardening and selective breeding for heat-resistant corals are helping reefs adapt to climate change. Local restoration projects, including Reef Stars programs in Indonesia (picture below) and community-led initiatives in the UK Overseas Territories, demonstrate how hands-on efforts can rehabilitate degraded reefs. High-level commitments, such as the UNOC3 Pledge, aim to protect climate-resilient reefs globally, while scientific tools like Wildlife Conservation Society’s global reef map and Adaptation Design Tool help governments and funders prioritise urgent protection. Together, these efforts show that coral reefs can recover and continue to support biodiversity and coastal communities.

The Final Message

The restoration and protection of mangroves, seagrass meadows, and coral reefs are essential for addressing biodiversity loss and climate change: providing carbon storage, coastal protection, and support for countless species. Across all three habitats, a common theme emerges: ecological health and water management are closely linked. All three habitats mentioned in this article both drive local ecological health and protect coastlines from erosion and flooding.

Safeguarding these ecosystems is therefore a responsibility for a broad community of practitioners. Members of CIEEM and CIWEM are uniquely positioned to collaborate, combining expertise in ecology, environmental management, and water resources to reinstate habitat benefits and mitigate ongoing threats. Working together across disciplines strengthens natural system resilience, protects biodiversity, supports local communities, and enhances climate adaptation. Coordinated action on mangroves, seagrass meadows, and coral reefs offers a pathway to meaningful progress against two of the most urgent environmental challenges of our time.

About the Authors

Athena Allen BSc (Hons), MSc, ACIEEM is a Marine Ecologist with NatureBureau Ltd. She also plays a key role in CIEEM, serving as Convenor of the Early Careers Special Interest Group and Secretary of the Marine & Coastal Special Interest Group, where she contributes to articles, webinars, and events on marine and ecological topics.

Athena Allen BSc (Hons), MSc, ACIEEM is a Marine Ecologist with NatureBureau Ltd. She also plays a key role in CIEEM, serving as Convenor of the Early Careers Special Interest Group and Secretary of the Marine & Coastal Special Interest Group, where she contributes to articles, webinars, and events on marine and ecological topics.

Roshini Mistry (CIWEM) is an Environmental Scientist at AtkinsRéalis with a focus on water resources and climate change. Having grown up in the tropics, Roshini has a keen interest in adaptation methods to support tropical marine ecosystems.

Roshini Mistry (CIWEM) is an Environmental Scientist at AtkinsRéalis with a focus on water resources and climate change. Having grown up in the tropics, Roshini has a keen interest in adaptation methods to support tropical marine ecosystems.