Nature Recovery Networks for Northern Ireland- More, Bigger, Better and More Connected Spaces for nature and people –By Nina Schönberg and Paul Armstrong

This blog has been written in conjunction with upcoming CIEEM 2023 Irish Conference: Aiming for a Nature Positive Ireland where Nina and Paul will be discussing the topic in more detail.

Our nature and climate are in trouble. With 11% of species threatened by extinction on the Island of Ireland, we desperately need a step change in how we protect and manage the natural environment. Locally designed but nationally and internationally coherent Nature Recovery Networks (NRNs) represent an exciting opportunity for making more space for nature, thus helping our biodiversity and climate to recover and bringing the benefits of a healthy natural world into every part of our lives.

The harsh reality is that people in Northern Ireland are living in one of the most nature depleted places in the world. In fact, research by the Natural History Museum and the RSPB revealed that Northern Ireland ranks 12th worst out of 240 countries when it comes to biodiversity loss (the Republic of Ireland just one space ahead at 13th), which has largely been driven by the fragmentation or even the complete loss of natural habitats. When species and their populations are restricted to remnant habitat patches and surrounded by inhospitable landscape, they’ll struggle to move and cope with and respond to any hazardous events or trends, including keeping pace with the degree of change brought by the changing climate. Therefore, there is an urgent need for us to look for transformative solutions that go beyond simply conserving existing habitats and species to actively restoring nature at a landscape scale. This should include the introduction of Nature Recovery Networks (NRNs) as a key delivery tool, as was recently recognised in the UK’s five statutory nature conservation bodies’ Nature-Positive 2030 -report.

©Northern Ireland Landscape Partnership

What are Nature Recovery Networks?

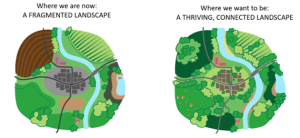

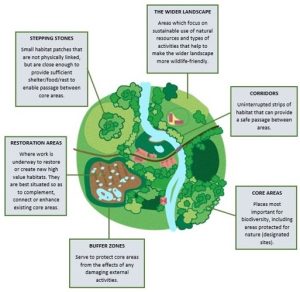

In short, NRN’s are a strategic, long-term approach to protecting, managing, creating, restoring, enhancing and connecting habitats and landscapes –linking together ecological processes across protected areas and the wider landscape while acknowledging that the status of our natural world is intrinsically linked with human well-being. Working with the principles of More, Bigger, Better and more Joined-up (often referred to as the ‘Lawton Principles’, based on the 2010 ‘Making Space for Nature-report) spaces for nature (and people!), the components of NRNs can be natural or man-made, and of any size ranging from green roofs to landscape-scale conservation projects. These physical features are summarised in the diagram below, where core areas and restoration areas are connected by corridors and stepping stones, surrounded by buffer zones and a nature friendly wider landscape, together which could eventually form a resilient and self-sustaining Nature Network.

©Northern Ireland Landscape Partnership

A brief history to NRNs

Globally, the understanding around the negative impacts of habitat loss and fragmentation and the need of well-connected habitat networks is not a new concept. The so called SLOSS debate (is a Single Large Or Several Small sites better?) emerged in the scientific community back in the 1970s, sparked by the introduction of the Theory of Island Biogeography. Further evolution of the thinking, especially in relation to the understanding of the interconnectedness and distribution of meta-populations and networks of ecosystems across the wider landscape supported the need of spatial ecological networks, especially in the context of long-term resilience under unpredictable environmental pressures, such as climate change. While the term ecological networks specifically, as a tool to influence land-use planning, has been around as a model since 1970s, it only really achieved credibility and wider application in the 1990s, IUCN adopting a resolution on ecological networks at the 1996 World Conservation Congress.

Nationally, Netherlands has really been the forerunner in the implementation of this concept, having worked on implementing the National Ecological Network since the 1990s but other countries, such as Estonia, Croatia and France have also advanced in their work on delivering connectivity as part of their conservation work, but challenges in setting standards and the forever changing political climate have hindered on the ground implementation. In the UK, progress has been more tangible since the influential 2010 ‘Lawton-report’, but in Northern Ireland, while the need has been recognised, limited progress has been made towards translating the concept into policy and practice to date.

Mapping More, Bigger, Better and More Connected habitat networks in Northern Ireland

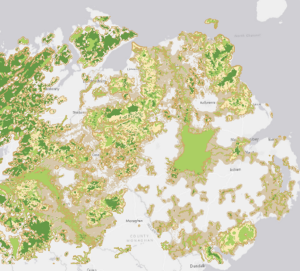

The combined national wetland network ©Northern Ireland Landscape Partnership

The successful implementation of the concept fundamentally relies on an effective delivery system, all aspects of which need to be working together towards a mutually agreed goal, nature’s recovery. One of the crucial steps towards this, is gaining a comprehensive picture of the current baseline that we are working with and were opportunities for the More, Bigger, Better and More Joined-up habitat networks might exist. Therefore, in 2021 the Northern Ireland Landscape Partnership (Ulster Wildlife, RSPB NI, Woodland Trust NI and National Trust NI), together with Environment Systems, and with generous funding from the National Lottery Heritage Fund, took on the task of mapping out what this might look like for Northern Ireland. Adapting a framework originally developed by Natural England, the aim for this piece of work (you can read the report here) was to provide the backbone for the evidence base for NRN design in Northern Ireland with a visual spatial expression of where potential might exist for on the ground delivery. The maps have since proven extremely useful for stakeholder engagement and project planning by partners and wider stakeholders alike.

NRNs helping to set ambitions for native woodland expansion in Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland has less than 9% (of which ancient woodland, which has been in existence since the 1600s, covers just 0.04% ) woodland cover, making it one of the least wooded places in Europe. The Climate Change Act (Northern Ireland) 2022 has set a target to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050. To meet this target, the UK Climate Change Committee has stated that that annual afforestation rates will need to reach 3,100 hectares by 2035 and 4,100 hectares by 2039, remaining at this level until 2050. This represents a substantial increase compared to afforestation rates delivered to date, which were on average around 290 hectares annually between 2018 and 2022. While these targets are driven by the need to capture and store carbon, it is crucial to note that climate change and biodiversity are inextricably connected, with climate change contributing to biodiversity loss and biodiversity loss making climate change and its effects worse. Therefore new woodland must provide benefits for wildlife as well as carbon capture.

Native trees and woods play a significant role in supporting Northern Ireland’s biodiversity. Therefore, protecting, restoring, and expanding native trees and woods must be a significant part of Northern Ireland’s response to climate change, to ensure the recovery and adaptation of its wildlife. This can be supported through spatially targeted actions such as buffer planting around ancient woodland sites and corridors to improve connectivity between patches of woodland to promote species diversity within a landscape.

Woodland creation at Glas-na-Bradan Wood in the Belfast hills. This 98 hectare site is being transformed into a new native woodland through the planting of 150,000 native trees. Projects like this will not only contribute to Northern Ireland meeting its net zero targets, it will create a valuable habitat for benefiting people and nature. ©Paul Armstrong

For this, the NRNs provide valuable set of principles and the datasets can help to ensure that the much-needed woodland expansion is delivered in the right places and in the right ways to capture and store carbon while simultaneously delivering wildlife-rich mosaics with other habitat types. Thus, the Woodland Trust is currently working with Environment Systems, utilising the National Habitat Network maps, to carry out a high-level study to establish a series of woodland cover targets and opportunity maps for Northern Ireland. It is hoped that these targets and opportunity maps will assist the government in setting and achieving ambitious tree planting targets that will create a sustainable future that benefits people, climate and nature.

Where next-what do we need to do to turn NRNs into a reality?

For NRNs to be successful in helping restore nature and provide for people, we need strong leadership and oversight from government. We need the approach to be adopted and associated frameworks and policies to be put in place across all government (including across public bodies) in order for NRNs to guide decision-making to prioritise opportunities to create, restore, and enhance habitats within and outside of Protected Areas network. For example, NRNs have the potential to strategically drive and spatially direct decision-making as part of future agri-environment schemes and planning system (linking up with Biodiversity Net Gain development). Furthermore, it is crucial for the nature recovery agenda to be intrinsically integrated with the upcoming actions from the NI Climate Act (2022), taking full use of the opportunities Nature-base Solutions provide.

Farmer on his species rich grassland meadow, which is particularly rich in Devil’s Bit Scabious, the main food plant of the threatened Marsh Fritillary butterfly caterpillar, Co. Fermanagh. Supporting farmers to maintain and create habitats like this under the future Agri-Environment Schemes will be key to NRN delivery. ©Peter McEvoy

There is already is and has been a lot of brilliant and exciting work underway on the island of Ireland to restore nature. NRNs should foster these existing local, regional and cross-border efforts to drive positive change across landscapes and the countryside, ensuring that these are scaled up and that all of the action are taken in a complementary manner. Fundamentally that’s what nature positivity, and nature recovery networks as part of it, is all about-making sure that we end up with more nature than we started with- and without coherent and bold action like this, we’ll struggle to get there.

Peatland Restoration in action at Cuilcagh Mountain SAC (under the CANN-project), a cross-border blanket bog on the South-West Fermanagh and North West Cavan Border. As the island of Ireland is essentially one biogeographical unit, cross-border initiatives and collaboration should be at the heart of NRN design and delivery. ©Simon Grey

To learn more about the work Ulster Wildlife and the wider Northern Ireland Landscape Partnership has been doing on Nature Recovery Networks over the last two years, including a suite of briefing notes and videos, click here to go to their website.

Book your Irish Conference ticket here

Nina Schönberg MSc. Is the Nature Recovery Networks Project Coordinator for the Northern Ireland Landscape Partnership, sitting at Ulster Wildlife

Paul Armstrong is the Public Affairs Manager for the Woodland Trust Northern Ireland

Blog posts on the CIEEM website are the views and opinions of the author(s) credited. They do not necessarily represent the views or position of CIEEM. The CIEEM blog is intended to be a space in which we publish thought-provoking and discussion-stimulating articles. If you’d like to write a blog sharing your own experiences or views, we’d love to hear from you at SophieLowe@cieem.net.