What does Transformative Change mean? – Diana Pound CEnv FCIEEM

Why do we need Transformative Change and what is it?

The interlinked crisis of climate breakdown, catastrophic loss of nature, and scale of social injustice are ever more urgent. We are exceeding planetary limits and triggering existential threats to life on earth. This is affecting all parts and people of the world and is the result of systemic and structural failures. In August 2021 The UN Secretary-General António Guterres said the IPCC report was nothing less than “a code red for humanity. The alarm bells are deafening, and the evidence is irrefutable”.

We urgently need transformative change!

But what does that mean? Transformative change results from profoundly changing both the way we make decisions and bring about change and the kind of impact that has. This is very different to what has been ‘business as usual’: narrow, linear, slow, piecemeal and incremental transition. We are out of time for that kind of slow paced change. Instead, transformative change requires a rapid and “fundamental, system-wide, reorganisation across technological, economic and social domains”[1] .

To be transformative decisions need to be made in new ways:

- Inclusive decision making to bring people with all relevant forms of knowledge to the negotiation (not just those with current power, interest and pre-existing capacity. This should be at an early stage whilst options are open. This approach is sometimes slower to get to decisions but then faster to implementation and change. The alternative, an ‘experts decide’ approach, overlooks crucial knowledge, fails to build buy in and often provokes resistance and stalemate.

- Integrated decision making across interests, sectors and levels of governance to align action and make the most of synergies, amplifiers and multipliers for net benefit for nature, climate and people.

- System Thinking to understand how the system behaves and where interventions will make the most difference. It means looking at system patterns, connections and how things unfold over time. This includes looking for: the reinforcing processes, the balancing processes that maintain equilibrium, nonlinear change, causal links and cumulative effects. It is then easier to see the intervention points that lever tipping points for virtuous and coherent outcomes. This is quite different from the current prevailing approach of thinking we understand what is going on if we try to sum the different parts.

- Harness all forms of relevant knowledge not just natural science and economic assessment – there are too many questions in decision making that neither can answer (such as: Is a proposal acceptable? Will it work for those most affected? Do they prefer it to another solution?). [2]

- Work with human nature knowing individual and group psychology to overcome barriers to change[3]

- Make implementation decisions at the lowest appropriate scale with those most affected sharing knowledge and insight into how things work at that scale so the effect of interventions can be seen with a systems lens to avoid unforeseen consequences and speed delivery.

Outcomes need to:

- Deliver in the ‘safe space’ on Katy Raworth’s doughnut diagram[4] (see Figure 1).

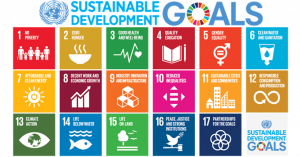

- Contribute to the delivery of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in a holistic package and at whatever scale you are working. Projects and initiatives can use them as a check list, seeking to meet and add benefit to as many as possible in a holistic way – as was intended (rather than either not even factoring them in or taking a pick and mix approach to concentrate on your favourites).

- Have high positive impact. This includes impact in both reach (the numbers of people, species, ecosystems, climate benefits affected) and significance (how significant the change). To achieve integrated benefits for people, climate and nature we need to ask all initiatives questions like:

- How many/much will benefit? Will it be few, local, area, country, nationally, internationally, globally? And how can we expand this?

- How significant will the effect be for human and natural life, ecosystems and climate (convenient, life improving, life enhancing. life changing)? And how can we amplify the significance?

- Last: the impact should be sustained and long lasting, or permanent – not temporary or unravel when the original initiative, project, programme, policy, or resources are over. This means designing in resilience, adaptive capacity, and future proofing (for people, nature and climate).

- Be socially just: addressing inequalities and human rights to ensure benefits of change are equitable and inclusive (factoring in gender, ethnicity, age, education level, local and if relevant indigenous people’s rights), and build social resilience[5], cohesion, agency to make a difference, and opportunity for those previously left out, at greatest risk, and disproportionally suffering the most degraded environments and conditions.

- Work locally on the ground –with local people holding power and resources to apply transformative change at a local level in a way that works for them, nature and climate right where they live.

Figure 1 Doughnut Diagram by Kate Raworth

Figure 2: The UN Sustainable Development Goals

What does this mean for environmental professionals, CIEEM, its members, and the work we do?

As a profession we need to transform our thinking, culture and ways of doing things and let go of linear thinking[6], narrow focus, natural science and technical solutions only, experts decide, risk averse, top down decisions and governance, onerous procedures, and incremental and small change.

We need to be more ambitious and act to: adopt Systems Thinking, do inclusive decision making to co-design and co-deliver non-linear change for multiple benefits, freely share knowledge and resources, harness creativity and innovation, be adaptive and flexible. And free ourselves from unhelpful systems and procedures that fetter our ability to change at pace. Then we can be nimble and able to support others in the urgent challenge we all face.

It also means acting and influencing for Transformative Change strategically. For example for: nature positive economies in UK countries, good quality of life through sufficiency and genuinely sustainable consumption, circular economy, rejection of GDP and replacement with an alternative based on wellbeing and intergenerational equity(because what we measure drives our attention and action), arguing and acting for nature to receive a great deal more climate funding (estimates are that nature can provide 30% of climate mitigation and adaptation but receives just 3% of climate funding).

Within our sphere it would include: acting so all projects result in net environmental benefit and regenerative land, water and marine management and use; ensuring initiatives such as the governments 30x 30 pledge deliver genuine rich nature not mere paper parks and are co-produced with local and, if relevant, indigenous peoples (not based on excluding fortress conservation[7] models); accelerating nature based solutions, green cities, and equitable and inclusive access to the benefits of green space.

| This is just an introduction and overview. We recommend CIEEM urgently considers what Transformational Change means for CIEEM: as an entity, for strategic work, and how to catalyse and amplify change working with and through CIEEM members at all the scales we work at. |

Figure 3 The IPBES (2019) Vision of intervention and leverage points for transformation[8]

Diana Pound CEnv FCIEEM

Diana has a background in protected area management on land and sea and 25 years’ experience of managing, designing and facilitating multi-stakeholder Consensus Building and Stakeholder Dialogue working at local, national, international and global levels, on a range of nature and climate related topics. Since setting up Dialogue Matters she has designed and facilitated over 120 processes and worked in 28 countries. She also carries out participatory research and provides advice to a wide range of organisations including Governments and International Bodies. Her work has won multiple awards and she was personally given the IUCN CEC Award for Excellence in West Europe in 2019 and second/highly commended in the highly prestigious UK Professional Environmentalist of the Year Award.

[1] 2020 Towards a sustainable future: transformative change and post-COVID-19 priorities A Perspective by EASAC’s Environment Programme. ISBN: 978-3-8047-4199-7. This Perspective can be found at www.easac.eu

[2] Unpublished – Dialogue Matters training on participatory systems thinking

[3] As above

[4] Kate Raworth, Doughnut Economics

[5] The ability of a social unit or group to tolerate, absorb, cope with, and adjust to external stresses, disruptions and disasters.

[6] Linear thinking is a natural human bias to thinking that one thing leads to another in a stepwise fashion and it comes with the related assumption that the fix to complex challenges is logic and rational analysis.

[7] Fortress conservation has its roots in colonialism. It is a top down approach to nature conservation delegitimising and curtailing or excluding human activities and traditional uses. This is not just about what happens overseas: some UK wilding projects have uncritically/unconsciously operated with these values towards local people.

[8] IPBES (2019). Summary for policymakers of the Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. Chapter 5. Pathways towards a Sustainable Future. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3553579

Blog posts on the CIEEM website are the views and opinions of the author(s) credited. They do not necessarily represent the views or position of CIEEM. The CIEEM blog is intended to be a space in which we publish thought-provoking and discussion-stimulating articles. If you’d like to write a blog sharing your own experiences or views, we’d love to hear from you at SophieLowe@cieem.net.